Art World

The Robot’s Hand? How Scientists Cracked the Code for Getting Humans to Appreciate Computer-Made Art

Seeking empathy with artists, people prefer art made by humanoid robots over other computer-generated works.

Seeking empathy with artists, people prefer art made by humanoid robots over other computer-generated works.

“Empathy is the new black,” someone said to me recently, referring to the trend in recent years to blame many of humanity’s most pressing problems on the depletion of empathy in today’s tech-mediated culture.

The phenomenon has reached the art world, too, perhaps most notably in the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s decision to open the world’s first Center for Empathy and the Visual Arts with a $750,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

It makes sense given that empathy is an idea that first got its start in the study of art. Nineteenth-century theorists described empathy as the way our bodies mirror movements in the external world. When the aesthetic philosopher Theodor Lipps watched a dance performance, he said he felt his body “striving and performing” with the dancers. Even with static works of art, observers “move in and with the forms” in such a way that triggers “muscular empathy,” wrote the German philosopher Robert Vischer,

More recent studies have shown that works of art with implied gestures, such as Lucio Fontana’s slashed canvases, increase activity in viewers’ motor and premotor cortices. “This ability to have the movements and experiences of the artists projected into our minds and bodies triggers an empathic response in the observer,” write the co-authors of a new paper in the journal Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, which looks at how our empathic responses to art are evolving in the age of artificial intelligence.

A work from Lucio Fontana’s ‘Concetto Spaziale’ series. Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

The study, “Putting the art in artificial: Aesthetic responses to computer-generated art,” asks whether viewers consider art, once considered a uniquely human activity, to be more or less valuable when it’s made by machines.

Previous research has found that observers tend to value the intentions of the artist more than a work’s subjective appearance. The qualities in a work most likely to be assessed are its uniqueness and whether it involved a high degree of physical contact with the artist. In keeping with these findings, the new study concluded that art generated by computers was ranked lower in aesthetic value than work made by people.

But there’s also a surprising twist. Viewers tend to elevate machine-made art when that machine is a robot, particularly an anthropomorphic robot, suggesting that humanoid embodiment may be the key to embracing a human-like mind.

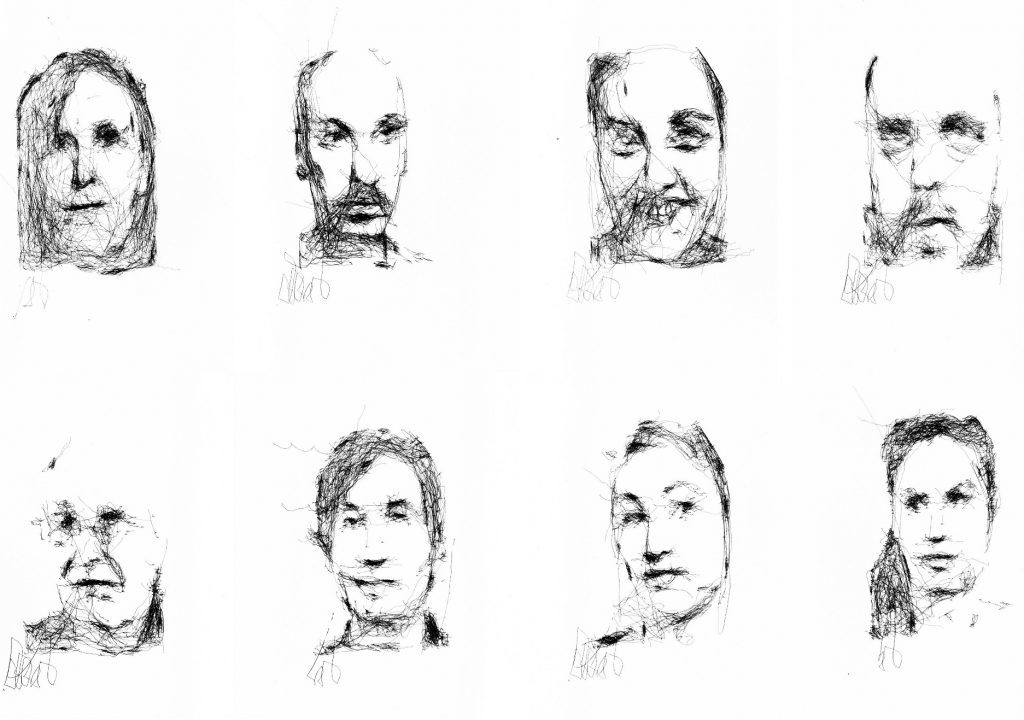

For the study, the researchers borrowed artist Patrick Tresset’s robotic installation 5 Robots Named Paul, which he showed at the BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels in 2015. The machines consist of webcams that take photos of sitters while a planar arm draws with a pen. Human-like figures are mounted to desks, reminiscent of students in a figure-drawing class, and enact life-like movements. They seem to look at the sitter and scan their face as the arm follows along, though in reality, they are purely decorative: The drawing results from a single photo taken at the start of the session.

Sketches by Patrick Tresset’s 5 Robots Named Paul (2014). Courtesy of the artist.

The researchers tested three different conditions: Some participants were in the room as the robots drew, others were only shown the drawings and told that robots had created them, and others saw the drawings but received no information about how they were made. The participants were then asked to fill out a questionnaire about the drawings.

The results found that those participants who saw the robot artists at work had more positive appraisals of the drawings. They appreciated them more than the drawings that were only said to be done by robots and more than those made by unknown artists.

“This is the first study to demonstrate [that] the anthropomorphism of an agent impacts positively on aesthetic appraisal,” the authors write. “[I]ncreasing the anthropomorphic qualities of robotic and computational art will increase societal engagement and likely decrease hostility toward future manifestations of artistic AI.” Translation: Making a computer look more human will make people more receptive to its art.

Paradoxically then, when it comes to the art of artificial intelligence, it may be the body that matters more than the brain.